Xetthecum Digital Ecocultural Mapping

IMERSS biodiversity informatics working group

February 1st, 2023

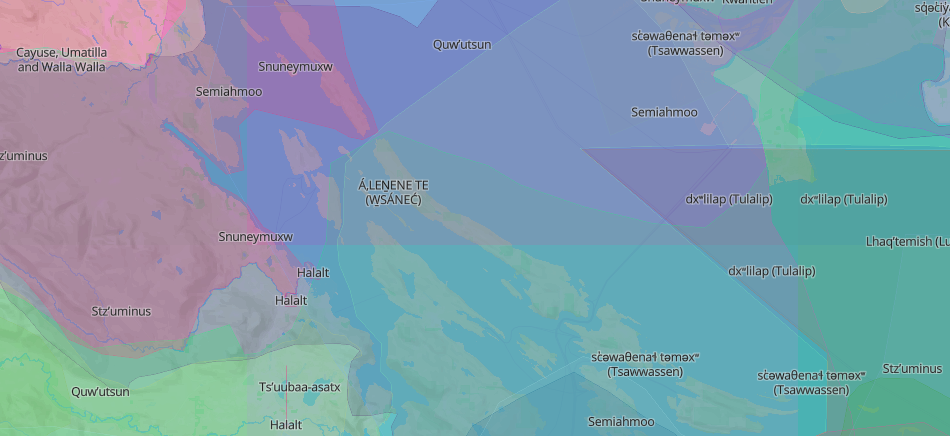

Land Acknowledgement

In the spirit of respect and gratitude, we acknowledge that Xetthecum (Retreat Cove), Galiano Island resides within the trans-boundary bioregion of the Salish Sea, a richly biodiverse expanse that has been tended to and cherished by the Coast Salish people since time immemorial. The island rests within the shared, asserted, and unceded traditional territories of the Penelakut, Lamalcha, and Hwlitsum First Nations, as well as the shared, asserted, and ceded traditional territories of Tsawwassen First Nation. Additionally, we acknowledge the territories of all other Hul’q’umi’num’-speaking peoples who hold rights and responsibilities in this region.

Introduction

Tth’i’hwum ‘i’ nuw’ilum tseep. Welcome to Xetthecum, an area on Galiano Island BC of ecological and cultural significance. Complex in its ecology, cultural history, and contemporary land-use, the boundary of Xetthecum is roughly delimited by the extent of the Greig Creek watershed, including the watercourse descending from Laughlin Lake to Retreat Cove, spanning residential and agricultural lands, protected and covenanted areas, and a public shore access.

Historic and Cultural Significance

Xetthecum is of important historical and cultural significance for the Penelakut peoples, once serving as a site for seasonal resource gathering as well as cultural and spiritual rituals and practices.

Sitting at the narrowest point on the island, Xetthecum is located at one end of a shore-to-shore route that allowed for important over-land travel across the island.

Xetthecum was a primary resource-gathering area. Penelakut elder Thiyaas (Florence James) and her family gathered an array of resources from this place, including berries, fruit, and shellfish as well as medicinal resources.

Ecological Communities

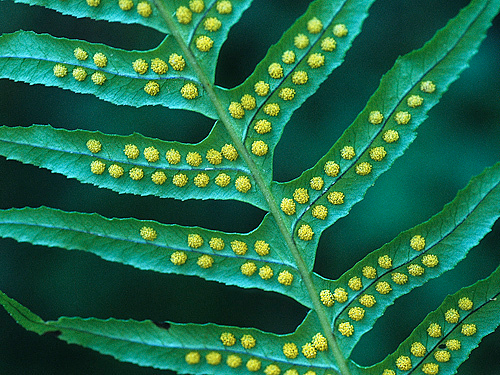

The Xetthecum region is made up of several ecological communities including Forest, Woodland and Rock Outcrops, Freshwater and Marine. Each of these ecological communities are home to a diversity of species, many of which are of particular cultural significance to the Hul’q’umi’num’ speaking peoples.

From the Lake to the Delta: Xatsa’ / Laughlin Lake

Laughlin Lake is part of a complex wetland ecosystem supporting a diversity of plant life, including culturally significant species like cattail (stth’e’qun) and fireweed (xáts’et). The riparian areas surrounding the lake are crucial for wildlife, offering habitat for species like black-tailed deer (ha’put) and great blue heron (smuqw’a’).

From the Lake to the Delta: Hwta’loonèts / Greig Creek

Grieg Creek was once home to abundant salmon which were an important source of food for the Penelakut peoples. Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities on the island are now working together to restore Coho and Chum salmon populations in the creek, primarily through stream bank restoration and salmon fry release by local schools. This activity is an educational and cultural experience for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children.

From the Lake to the Delta: Delta

The Greig Creek delta was once home to significant clam gardens, which were an important food source for the Penelakut people, and clam digging was an important cultural activity. Due to ecological disruption caused by resource extraction, development, logging, and agriculture, the clam gardens have been replaced by a large and invasive oyster bed which is visible at low tide.

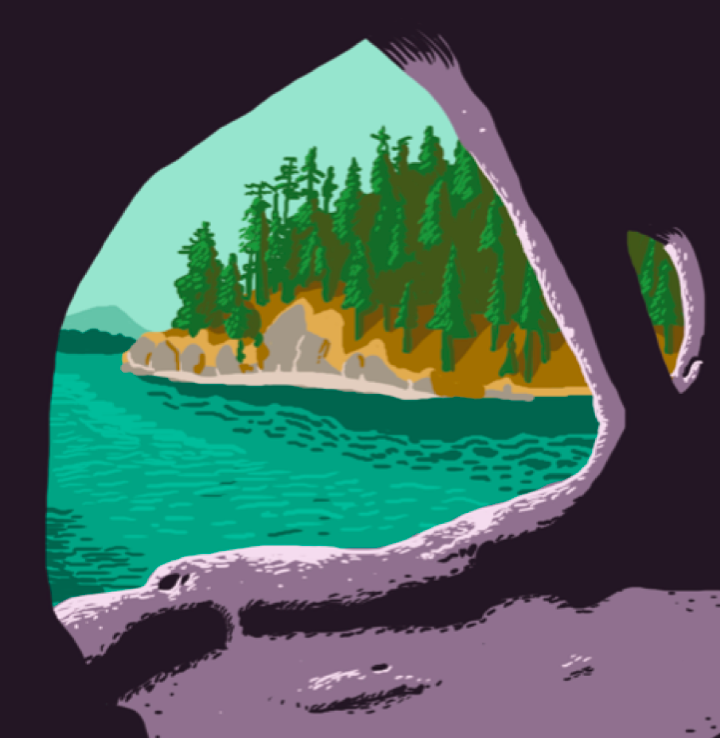

Life at the Cove: Caves

The caves at Xetthecum have significant spiritual and cultural significance for the Hul’q’umi’num’ speaking peoples of this region. Retreat Cove, including its caves, served as a location for private ceremonies for the people of Penelakut. Penelakut elders have emphasized the need to protect and respect these important cultural spaces; until now, the caves have not been protected and are at risk of being damaged by vandalism and overuse as a result of tourism.

Life at the Cove: Retreat Cove

When travelling by boat, the cove was a place where one could take refuge in a storm.

Xetthecum was important for social and cultural gatherings, as well as for traditional activities such as fishing and clam digging. Lorne Silvey

As a marine location, Retreat Cove is a habitat for rockfish and has been significant for fishing, but it is now a marine protected area to conserve these species due to overfishing and habitat destruction.

Life at the Cove: Eelgrass Beds

Lying near the mouths of Greig Creek (Hwta’loonèts ) and Davidson Creek,the eelgrass beds at Xetthecum are an important marine ecological community. Eelgrass is a foundational species that creates a complex habitat, thereby providing shelter for a large number of diverse species, from microscopic bacteria and algae to larger animals like crabs, fishes and birds.

Eelgrass meadows, kelp beds (q’am’) and coastal marshes are massive carbon sinks, absorbing CO2 at a rate of up to 90 times that of forests on land. Protection and conservation of these areas is thus important not only for biodiversity and marine species health, but also for worldwide climate change mitigation.

Ecosystem and Environmental Significance

Community Connection

The stories of the elders highlight the intimate connection between the community and Xetthecum. This connection is brought to life through the cultural practices and traditions associated with the area.

Preservation Efforts and Future Vision

Xetthecum is a vital marine sanctuary and a protected area crucial for preserving rockfish and shellfish populations. Restoration initiatives coupled with approaches that follow Indigenous wisdom and practices will help to safeguard the area’s resources for future generations.

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities are actively involved in preserving and reconnecting with the land through educational initiatives and conservation projects, aiming for a sustainable future vision for Galiano Island.

May our work on this project and presence on this island contribute to a future that recognizes the importance of reconciliation, collaboration, and the rightful place of Indigenous knowledge in shaping the well-being of the Salish Sea and its inhabitants.

Shaped by interactions between water,

soil, terrain, climate and the multitudes of beings that live within

them, forests are a sanctuary for hundreds of thousands of species of

plants, fungi, mammals, birds, insects and microorganisms. Forests

provide shelter, clean water, and food, the foundations for a complex

web of life in which we are intricately connected. Humans have been

stewarding forests on Galiano since time out of mind, in order to ensure

key species that we depend on can flourish and help us thrive.

Shaped by interactions between water,

soil, terrain, climate and the multitudes of beings that live within

them, forests are a sanctuary for hundreds of thousands of species of

plants, fungi, mammals, birds, insects and microorganisms. Forests

provide shelter, clean water, and food, the foundations for a complex

web of life in which we are intricately connected. Humans have been

stewarding forests on Galiano since time out of mind, in order to ensure

key species that we depend on can flourish and help us thrive. Healthy wetlands, lakes and

streams are havens for humans and wildlife alike, providing critical

habitat and a source of freshwater. A diversity of plant life, bacteria

and insects thrive in these ecosystems, forming complex food webs that

support many culturally important species, such as stseelhtun (salmon).

Thuqi’ (sockeye salmon) and haan (pink salmon) are two types of salmon

favoured by Indigenous community members on Galiano. In addition, the

enhanced growth and forest structure found in riparian areas provides

necessary cover for wildlife, which is also important for culturally

significant activities such as hunting and birdwatching.

Healthy wetlands, lakes and

streams are havens for humans and wildlife alike, providing critical

habitat and a source of freshwater. A diversity of plant life, bacteria

and insects thrive in these ecosystems, forming complex food webs that

support many culturally important species, such as stseelhtun (salmon).

Thuqi’ (sockeye salmon) and haan (pink salmon) are two types of salmon

favoured by Indigenous community members on Galiano. In addition, the

enhanced growth and forest structure found in riparian areas provides

necessary cover for wildlife, which is also important for culturally

significant activities such as hunting and birdwatching.

Often known as Garry Oak Meadow

ecosystems, a decolonized perspective prioritizes not the largest or

most visually obvious species, P’hwulhp (Garry oak - named for a

Hudson’s Bay Company officer, Nicholas Garry, by botanist David

Douglas), but instead the most culturally significant species, speenhw

(blue camas). Fields of speenhw have been cultivated for thousands of

years by First Nations Camas Keepers throughout this region, creating a

unique ecosystem that is not found anywhere else in the world. Like

speenhw, stl’ults’uluqw’us (chocolate lily / tiger lily) are very

beautiful and edible. Other culturally significant species include

t’uliqw’ulhp (yarrow) and q’uxmin (barestem desert parsley / wild

celery), which are prized for their medicinal qualities.

Often known as Garry Oak Meadow

ecosystems, a decolonized perspective prioritizes not the largest or

most visually obvious species, P’hwulhp (Garry oak - named for a

Hudson’s Bay Company officer, Nicholas Garry, by botanist David

Douglas), but instead the most culturally significant species, speenhw

(blue camas). Fields of speenhw have been cultivated for thousands of

years by First Nations Camas Keepers throughout this region, creating a

unique ecosystem that is not found anywhere else in the world. Like

speenhw, stl’ults’uluqw’us (chocolate lily / tiger lily) are very

beautiful and edible. Other culturally significant species include

t’uliqw’ulhp (yarrow) and q’uxmin (barestem desert parsley / wild

celery), which are prized for their medicinal qualities.

Ecological Community: Freshwater #### Species commonly found at

Laughlin Lake

Ecological Community: Freshwater #### Species commonly found at

Laughlin Lake

Ecological Community: Freshwater

#### Species commonly found at Greig Creek

Ecological Community: Freshwater

#### Species commonly found at Greig Creek